In June 1940, England was alone against Hitler. With Western Europe in the hands of the Führer, the United States still out of the conflict, and the Soviet Union committed to a non-aggression agreement signed in August 1939, there was no one capable of supporting the British.

Germany had the largest Air Force in the world and was spurred on by the acachapante victory in France. On the other hand, the British had better armed planes and a tradition of preventing access for any and all invaders since 1066 – that year the Duke of Normandy, William I, won the Battle of Hastings and, for only a few months, took England from the British for the last time.

In 1940, in the air battle between Germans and British, important English centers were heavily bombed, and the country came close to defeat. But, slowly, England resumed its space thanks to the stoicism of its people and also to the domination of a recent invention: the radar technology.

Initiated on July 10, 1940, the Germanic attack lost strength on October 31, 1940, and was definitively terminated in May 1941. After 11 months of torment, England was devastated, but standing.

By mobilizing the German Air Force, the Luftwaffe, just a month after France’s defeat, Hitler wanted to take advantage of the allied chaos to destroy Britain’s air defenses and thus facilitate a ground invasion – or, perhaps, force the British to call a truce. From the northwest coast of France, the Netherlands and Norway, 4,000 men left in 2,800 aircraft bound for England.

On the front line were two air groups, Luftflotte 2 and Luftflotte 3, which had been decisive in driving the blitzkrieg on continental soil. But now the fight would be different. For the first time since the beginning of the war, German aircraft would not only support the ground forces. The whole battle was in their hands and that of their commander Hermann Göring.

The British Royal Air Force (RAF) had lost more than a thousand aircraft in France and Norway. This represented two-thirds of all new aircraft built since the war began in 1939. The great allied asset was the most developed radar system in the world, coordinated by Air Marshal Hugh Dowding, the head of the RAF’s Fighter Command.

With the radars, it was no longer necessary to make long reconnaissance flights. It was enough to wait for the right moment and act directly against the enemy, wherever he was. The Germans, in turn, were very badly equipped by the intelligence service. They underestimated the real firepower of the British, and during the conflict they even attacked several airports that were not even used for the war effort. When the open confrontation started, the giant Luftwaffe was short-sighted – and did not know it.

First attacks

The Battle of Britain had five very distinct phases. In the first, which lasted from July 10 to August 8, German forces made incursions on the British south coast. Diving bombers acted against merchant ships from the English Channel and attacked some coastal towns in the Dover to Plymouth strip.

It was a bad start for the English. The German fighters acted in formations of four aircraft, with two at the front and others at the rear, while the English maintained a more antiquated and counterproductive battle structure, in which two planes did the defense of only one.

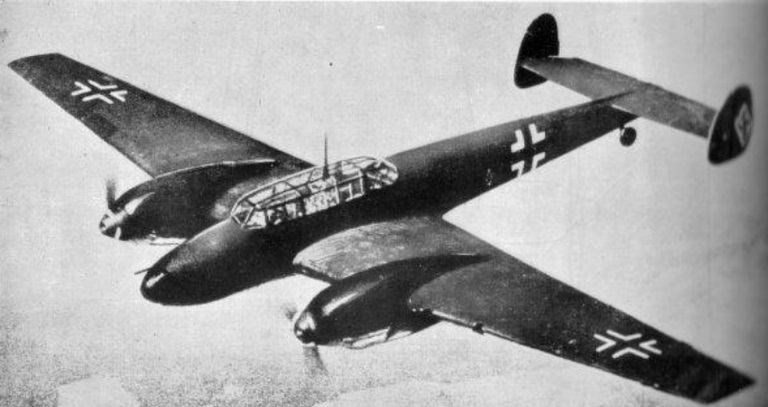

But, after two weeks of German success, the bad weather caused a five-day truce. It was enough for the RAF to reorganize itself. In August, the Germans had lost 217 planes, against only 96 of their enemies. The Luftwaffe was beginning to realize that some of their artifacts, like the Messerschmitt Bf110 fighter and the Junker 87 diving bomber, were too slow for air battles. The English, in turn, ran to change their war formations.

At the second moment of battle, the Germans tried to reduce the enemy fleet with fighting in the air, hunting against hunting. British losses were considerable: 286 planes, against 208 of their rivals. But, for the second time, the closed time forced a pause of one week. At the end of that phase, the British scored points in the psychological war.

After an accidental bombing in the suburbs of London, the British reacted with a rapid attack on Berlin on the night of August 25. The Germans, who considered their capital inaccessible to the enemy, got scared. On the same day, they began a third wave of attacks.

This time the targets were widespread: fighters in the air, but also ground bases, civilians and military. It was there that the flaws in German intelligence caused a compromising error: the British radar system was hanging by a thread, but the Germans did not notice. Impressed by the loss of 378 airplanes, they changed their strategy once again, to the relief of their opponents.

Civilian targets

Once again, the initiative to change the course of the conflict came from the Germans. From September 7, the blitz against the cities began. The skies of London were flooded by 300 German bombers, escorted by 600 fighters. Despite the delay in reacting, the RAF managed to contain this first movement, at a cost of 28 fighters down.

The Germans, in turn, lost 41 planes. And the capital ended the day with 450 dead and 1,300 wounded. New attacks occurred in the following days, until, on September 15, a great British victory made the Germans realize, for the first time, that England would not surrender. The German pilots, who since July had heard from their commanders that the RAF was by a thread, were exhausted.

On the 18th, the British took the initiative for the first time and drove their enemies away from the vicinity of the capital. Then began the fifth and final phase of the battle, marked by English rule and the retreat of Göring’s forces. Until October 31, each Germanic plane that dared to fly over the British territory was pursued.

Although eventual incursions extended until May, Hitler had already given up on England. When he did, he gave preference to civilian targets – on December 29, for example, 3,000 people were killed in London. Until the end of World War II, the Luftwaffe would never be the same. While the Führer was beginning to turn to Eastern Europe, Winston Churchill was using victory to get the United States more involved in the conflict.